The most sought after office in the world, that of the United States president, understandably comes with fierce competition. Advantages and weaknesses are assessed, reassessed, and exploited, ultimately seeking to extinguish competitors’ chances. One method that has been addressed in the 2016 presidential elections draws upon candidates’ eligibilities for who constitutionally qualifies as a “natural born citizen.”

In 1968, George Romney’s status as a “natural born citizen” was challenged, being born in Mexico. The issue was brought up again in 2008, with John McCain’s candidacy, born in Panama, throughout President Obama’s two terms, and recently looking at GOP candidates Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and Bobby Jindal. The matter of who constitutes a “natural born citizen” should be straightforward, but oddly, it’s not. Here’s where the confusion lies:

Obviously those born outside of the country are not “natural born citizens.” But wait. What if their parents are US citizens? Suppose expecting parents leave the country for the support of a family member in Canada, bear a child there, and then return. Should that render the child ineligible for the office of president? What if only one parent is a US citizen? The answers to these questions are not clarified by the Constitution, and the Supreme Court has yet to chime in.

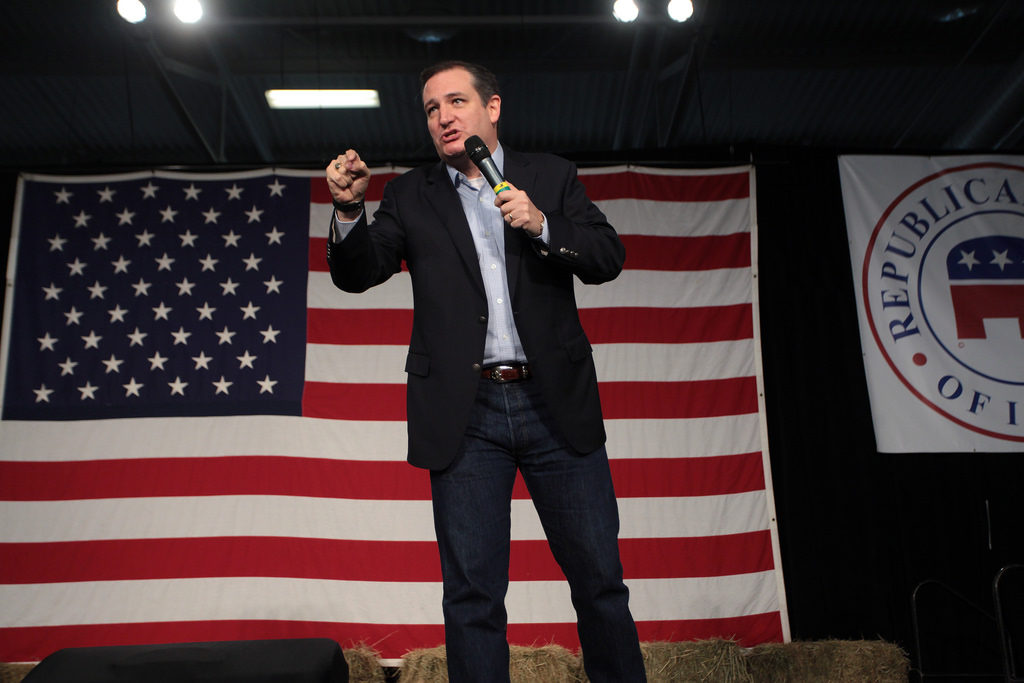

The current elections possess an even better, mind bending scenario with GOP candidate, Ted Cruz. The candidate was born in Canada to an American mother, and a Cuban father. His father later gained US citizenship. Complexity thickens learning that Cruz’s mother took a Canadian naturalization oath before his birth, which very well resulted in the loss of her US citizenship. With potentially neither parent a US citizen when Cruz was born in Canada, is he eligible to fill the office of president?

It’s not likely we’ll find out through the courts. Any citizen can file a complaint, starting the process, but there are a few problems. One of them is that even with a judge assigned, the petitioner must prove injury is caused to them by the candidate’s presidency. Despite several separate but similar suits, cases won’t strengthen each other. Judges are frankly not likely to take them. Many legal scholars indicate that it would thus require a presidential candidate to claim injury, which is still a difficult claim to prove.

A method observed in the current elections is the demand for a declaratory judgment to ensure competitors’ eligibilities. These are invalid requests as judges issue declaratory judgments with active cases. Instead, the most likely way for Constitutional clarity is through the candidate in question suing a state elections commissioner that has disqualified them from participating in a primary or caucus. As that hasn’t happened, and the Supreme Court is not in a place to prioritize it, we’ll just have to wonder.